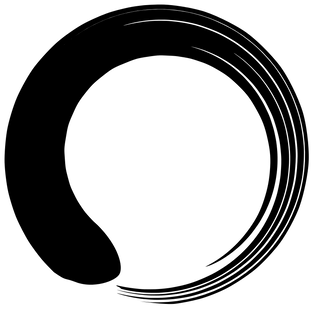

This piece (covering Vol 2) follows Revisiting the Jataka Morals – 1 posted in May on the Buddha Day. Before moving on to start with it, I like to briefly delve into three of the stories (18, 19, 50) presented in that piece (and 77 in this piece) – where the compassionate Buddha - The Tathagata (624 – 544 BCE) has drawn attention to the cruelty of ritualistic sacrifice of animals to please gods and goddesses. His teaching says to refrain from such practices of volitional killing – by respecting the rights to live by all creatures. Such repeated references indicate that the practice was common in greater India Sanatana Dharma (came to be known as Hinduism at later times), for that matter in most Shamanic and other ancient religious practices. The post-Buddha Hinduism has abandoned the practice, although some pockets of sacrificial rituals continue to occur in isolated rural areas. In his 1887 Novel Rajarshi – Rabindranath Tagore (1861 – 1941) lucidly sketched the story of a conspiracy to unseat a ruling king who dared to ban ritual animal sacrifice in his kingdom. The conspiracy hatched by Hindu priests together with Muslims – plotted to overthrow the government in collusion with the king’s younger brother. . . . Among the stories summarized in this piece, perhaps the following seven stand out in terms of their exclusive references to individual perfection – and to good social interactions and governance: (1) 66 and 251, a ruler is required to provide four basic necessities to subjects; (2) 68 and 237, interconnectedness of all; (3) 70, conquering oneself is the key to practice, and live in the abode of the Four Sublimities; (4) 72, the ten perfections that define a great human being; (5) 84, the six ways to become worthy; (6) 95, the ten rules of good governance; and (7) 99 and 101, the difficulty of understanding Sunyata or Emptiness. The last one was difficult to understand during ancient times – as it is now. Emptiness is meaningful in the context of space or spacetime – of the spacetime of mind, body, social interactions and the universe – saying that the dynamics of spacetime are empty of something – something definitive. Because what is space is meaningless without form, and vice versa. The Buddha referred to the world’s earliest (~ 1000 BCE – 5th CE) university at Takkasila (or Taxila, in present day Pakistan) in the Jataka Tales (e.g. 61) – as an institution where people from around the world came to learn. During the post-Buddha period, this university together with the 2nd earliest (427 – 1192 CE) university at Nalanda – acted as educational and research centers of science, mathematics, philosophy and Buddhism – and is believed to have given birth to the Mahayana school. Located within Takkasila is the ruin of the great Dharmarajika Stupa – where precious Buddha relics were housed. . . . Stories of Moral Strengths Told by the Buddha 51. King Goodness the Great. A goodness king triumphed in the end by following righteous policies Trust the power of righteousness without fear. 52 and 539. King Fruitful and Queen Sivali. The long story of a king giving up his power There are many things one can learn from people of all walks of life. Giving up power is more difficult than gaining and holding on to power. 53. A Gang of Drunkards. The drunkards could not fool a sober person Remain sober by using your common sense, to not fall into the trap of addiction. 54 and 85. The Whatnot Tree. The story of a wise merchant Always test the water before jumping in. 55. Prince Five-weapons and Sticky-hair Monster. A valiant prince subdued a monster by virtuous talks All have the true weapon of virtues inside them to confront and change others. 56. A Huge Lump of Gold. A poor farmer used his wisdom to uncover buried treasure Do not promise more than you can deliver. 57 and 224. Mr. Monkey and Sir Crocodile. A clever monkey outwitted a crocodile When lost one can still win the heart of others by respecting and admiring the winner. 58. A Prince of Monkeys. A monkey king failed to kill his rival by trickery A person of skill, courage and wisdom is unbeatable by enemies. 59 and 60. Two Ways of Beating a Drum. An ignorant drummer overdid his beating All things have to be measured, overdoing brings one’s downfall. 61. Two Mothers. A mother sends her son to Takkasila to earn unhappiness degree Honesty is important for couples living happily together. 62. The Priest who Gambled with a Life. The story of testing faithfulness Faithfulness must come from one’s character, it cannot be forced. 63. The Wicked Lady and Buttermilk Wise Man: The story of wicked seduction Be aware of being tempted into wicked seduction. 64 and 65. Country Man and City Wife. The story of a student learning about the fact of life It is wise not to be angry at things one does not understand and have no control over. 66 and 251. The Wisdom of Queen Tenderhearted. A queen used her wisdom to save a priest from doing mischief A righteous ruler ensures four basic necessities for subjects: (1) food; (2) clothing; (3) shelter and (4) medicine. The pangs of desire enslave, only the light of wisdom has the power to liberate. 67. A Wife and Mother who was Sister First. The story of woman choosing to save her brother first. Intelligent response helps one to overcome the difficult situations. 68 and 237. 3000 Births. Interconnectedness of all One way or another, we are all related. 69. The Strong-minded Snake. The story of a stubborn snake earning admiration Determination wins admiration and respect. 70. The Shovel Wise Man. An ordinary shovel man teaches the power of Sublimities The best of all triumphs is conquering oneself. It lets one to live in the abode of four heavenly states of mind: Love, Compassion, Joy and Equanimity. 71. The Wood Gatherer: The story of a lazy student Do not put off until tomorrow what you can do today. 72. The Elephant King Goodness. The story of an ungrateful greedy man A great being is defined by the embodiment of Ten Perfections: (1) Energy; (2) Determination; (3) Truthfulness; (4) Wholesomeness; (5) Balance of Attachments; (6) Equanimity; (7) Wisdom; (8) Patience; (9) Generosity; and (10) Loving-kindness. Reciprocate in gratitude what you owe to others. 73. Four on a Log. The story of an ungrateful arrogant prince Even animals understand the virtue of gratitude, while humans fail. 74. New Homes for the Tree Spirits. The story of tree spirits Fools are deaf to wisdom. 75. The Fish who worked a Miracle. The story of a virtuous fish saving all from drought The sincere efforts of virtuousness are rewarded in ways no one thinks possible. 76. The Meditating Security Guard. Fearlessness of a simple guard Sublime qualities of Loving-kindness, Compassion, Joy and Equanimity make a person fearless. 77. Sixteen Dreams. In four-part tales, a king described his sixteen horrific dreams with fear for his life and the kingdom, and yielded to the advice of priests to conduct a huge sacrifice of animals. But a holy monk saved the king from unwholesome sacrifice by interpreting that dreams as horrific as they are will come true in the future, when there will be no righteous wholesome deeds. Instead things will be managed by greed and malice. Perhaps the wrath of violence, pain and chaos portrayed by the brush strokes of Pablo Picasso (1881 - 1973) in his Guernica painting is somewhat like a modern vision of what the king saw in his dreams. The future can be grim when continuous pursuance of unwholesomeness and greed takes control. They not only cause detrimental impacts on people and society – but also ushers in irreparable degradation of Nature and Environment. 78. Illisa the Cheap. The story of a miser Poor indeed is a wealthy person who is unfair and shares nothing with others. 79. A Motherless Son. A headman betrays the trust of villagers A betrayer is trusted by none, sometimes not even by his or her mother. 80. Fear Maker and Little Archer. The story of how outside look can be deceitful and how vanity can destroy a person Be careful, outside appearance can be deceiving. Stand up to what you earn without being vain. 81. Forest Monk in a King’s Pleasure Garden. The story of novice monks getting drunk The young needs guidance from the elderly and learned. 82. The Curse of Mittavinda. Same story as 41 83. None included in the compilation 84. A Question from a Seven-year-old. A fathers advises his son of six worthy ways The six worthy ways: (1) keeping healthy and fit; (2) being wholesome in every way; (3) listening to the experienced; (4) learning from the knowledgeables; (5) living according to the truth and; (6) acting with sincerity and energy. 85. None included in the compilation 86, 290 and 362. Lesson from a Snake. The story of a priest learning from the behavior of a snake Goodness demonstrated by the virtues of Panchsila is admired and prized by all sentient beings. 87. A Priest who Worshipped Luck. The story of superstitious priest Good or bad luck does not depend on jewellery or on what one possesses, but on what one does. 88. The Bull called Delightful. Same story as 28 89. The Phony Holy Man. The deception of a holy man to his trusted devotee Be vigilant, deceptions could come from apparently trustworthy individuals. 90, 363. One Way Hospitality. The story of ingratitude Hospitality and gratitude do not work one way – they must be reciprocated. 91. Poison Dice. Gambling trickery got caught Honesty wins all, even the gamblers. 92. The Mystery of the Missing Necklace. The story of how criminals implicate others through lies that cascade from one to the next Greed breeds lies and thievery to trap all into the dragnet of disasters. 93. The Careless Lion. Fascination cost a lion’s life Do not let fascination blind you of dangers. 94. The Holy Man who tried to be too Holy. The story of a holy man who believed suffering makes one holy No one benefits and finds peace from suffering, not even the holy ones. 95. Clear-sighted the Great, King of the World. The story of a great king who ruled following the Ten Rules of Governance, heeding to Panchsila, and Mindfulness for happiness of all on the paradigm of the Law of Transience. Great leaders follow the Ten Rules of Governance: (1) no ill-will to any; (2) no hostility to any; (3) no harm to any; (4) having self-control; (5) having patience; (6) being gentle; (7) practicing charity; (8) practicing generosity; (9) being straightforward; and (10) practicing goodness. 96 and 132. The Prince and the She-devils. The story of a young prince who conquered the temptation of enchantment and attraction caused by the five senses. He upheld the virtues of the Ten Rules of Governance and the Four Ways to avoid going astray. Be watchful of your own five senses because they could mislead you by getting trapped into the lure of enchantment. A wise ruler must rise above (1) prejudice, (2) anger, (3) fearfulness and (4) foolishness. 97. A Man Named Bad. A dissatisfied man realized names are no indications of the person A rose by any other name smells as sweet. 98. A Man Named Wise. The story of how a person named Verywise was caught cheating by another named Wise Do not judge people by their outward appearance. A rogue by any other name remains as harmful. 99 and 101. Achieving Nothing. The story of how disciples could not understand the master’s last words about emptiness. In the tangled ball of interdependence, each entity by itself amounts to the Emptiness of essence. 100. A Mother’s Wise Advice. A queen mother advises her son how to win a war without violence. Explore alternative ways to win a war without violence and fighting. . . . I like to spend a little time on Emptiness (and selected a popular image of it, credit: anon) in an attempt to unravel the beauty of it. This particular image is thoughtfully drawn to express the meanings of Emptiness and associated Buddhist ideals. In the image, the brush stroke swirls in a clockwise direction (the direction represents Buddhist aspiration for stability and unity) to depict an incomplete circular space that conveys the message of imperfection, a lacking piece or a missing link. Search for this missing link is what drives the system of universal interdependent fluxes of things – and is an indication of Emptiness (delivered in the Perfection of Wisdom Discourse or The Prajna Paramita Heart Sutra). It accompanies the dynamic process of continuous efforts to fill the void of Emptiness – and is a logical conclusion of the two Universal Laws the Buddha proclaimed – the Law of Transience (Anitya or Impermanence), and the Law of Dependent-origination (Paticca-Samupadha or interdependence). Buddha’s teaching stands on these Natural Laws to direct human efforts in the Right direction to fill the void of Emptiness – to happiness and enlightenment. Let us attempt to see more of it briefly. Buddhist monks and scholars explain Emptiness in different ways depending on their personal convictions, but they all lead to the same meaning. One such interpretation is superbly worded in Zen Buddhism: empty the mind to see things as they are. This saying sees emptiness as part of Zen meditation practice – as emptying the mind of what are hindering it (see Meditation for True Happiness) from concentrating and becoming calm. Here emptiness is interpreted as a method of getting out of the cobweb of unhappiness. Let me attempt to unravel the truth of Emptiness from my own work experience – from the physics of wave motion, or wave dynamics (see Ocean Waves; Linear Waves; Nonlinear Waves; Spectral Waves; and Transformation of Waves). Ocean waves are most visible in the dynamics of wave crest and trough, and all the irregularities associated with the processes. At least four inherent characteristics define the wave: (1) the wavy distortion of water mass is in response to transporting some gained energy; (2) the energy is imparted into the water mass through its interfaces with air, ground, or other masses of different densities; (3) as soon as the wave is born it is subjected to interactions giving birth to new frequencies, and becomes spectromatic; and (4) that a visible wave is in fact built by a multitude of waves of different frequencies and amplitudes. Each of these items is a reality or the conventional truth – yet by itself none of them defines the wave form. This implies that a conventional truth is incomplete – and therefore, by itself is empty or empty of essence. . . . What is essence? The meaning of essence or substance can be defined from different viewpoints – and there are many rooms for one to be creative. Let us think of two. The first one is rather obvious – that if everything is in flux of interdependence – the idea of the constancy of soul (Upanishadic Atma) cannot exist, and is thereby empty of essence. Therefore, the Buddha defined a transformative soul (Anatma or no-soul in conventional meaning) of noble qualities that accumulate over time in an individual. Termed as Bodhi or Buddha-nature (delivered in the Lotus Sutra) – this entity is the light one must always look back for answers and wisdom in calmness of mind. The second is the known fact of human experience – of the absence of desirable degrees of Happiness in human mind – such that it always eludes an individual’s aspiration – like a drop of water in the slippery lotus pad. Buddha’s teaching – the Jewel in the Lotus – tells one how to add essence to happiness by making efforts (but without craving for happiness) to lengthen it (see Meditation) through the practices of three Purities: the Purity of Mind, the Purity of Morality and the Purity of View. Presence of Emptiness means the system grinds to complete the wheel in search for equilibrium. Buddha’s teaching is a guidance (Yana or Vehicle) for working forward to find that equilibrium by inquiring into one’s own Bodhi – through the wisdom eye. Here is a very interesting story – how the Buddha used different innovative methods to teach some queries. He did this, based on his assessment of the mind-set of the questioner. It is said that some ardent believers of God, prayed to the Buddha to show the presence of God. Buddha told them to walk with him around the campus to find God. Buddha made several rounds with them – finding none, the Buddha said: See, it is all Empty. And, it makes sense. The Buddha then taught them: If you believe in God, don’t waste time searching somewhere else. You must try to find within you – the Bodhi-Citta that resides in all of us. This process leads to enlightenment – and if a person is able to reach the tranquility of perfect equilibrium – he or she achieves something sublime and extraordinary. Buddhism calls it Nirvana. Emptiness and Nirvana are two supermundane truths in Buddhism – the former defines the grinding fluxes in the universe of mind, social interactions and everything else – characterized by Transience and Dependent-origination – while the latter is an aspirational goal to achieve eternal bliss. In Nirvana . . . there is no cause, no arising, no birth, no decaying, no demise, and no rebirth – everything is in complete balance without residuals – in the eternal tranquility of universal unity. . . . Deep philosophical and spiritual thoughts and principles – such as Emptiness, Nirvana and the transformative nature of soul – which are often difficult to understand – have attracted many scholars, debaters and rulers to challenge Buddhism over time. One of the most important ones – was the Buddha’s encounter with his top disciple Sariputra. Sariputra was a very learned Brahmin and came one day with 500 of his followers – and lots of fanfare to challenge the Buddha and defeat him in the debate. It is said that the Buddha calmly welcomed Sariputra by telling him about a condition before starting the debate. The condition was that Sariputra had to listen to the Buddha’s deliverance first. With the agreement in place, the Buddha started with the Natural Laws on which his teaching was based – then with the rationality and wisdom of the Four Noble Truths and the Noble Eightfold Path (see Happiness). By the time the Buddha finished the deliverance, Sariputra was already in submission to the Buddha’s authority, and prayed to the Buddha to ordain him and his followers. The Buddha blessed Sariputra by saying: tathastu (so be it). A similar challenge happened nearly half a millennia later in the 1st century CE between the Bactrian King Milinda (or King Menander as known in history book as the ruler of Bactria in modern northern Afghanistan; King Menander was a General in the army of Greek Buddhist King Demetrius – who invaded India in 184 BCE after the fall of the Great Mauryan Empire – and the rise of Brahminic Pushyamitra Shunga Dynasty. The rulers of this dynasty have resorted to persecuting Buddhists and destroying Buddhist establishments – thus invoking anger in the Greek rulers. The Buddhist rulers of Demetrius and Menander are credited to have presented the Greek style Buddha image – as it is prevalent and popular in the world today) and a monk named Nagasena (Milinda Panha in Pali text Buddhist scripture, and a version in Chinese text. see The Debate of King Milinda by Bhikhku Pesala, Buddhanet.net 2001). The conversation took place in the format of Greek intellectual dialogues with Nagasena assuming the role of Socrates (470 – 399 BCE). The calm and eloquent answers and deliverance by the monk elevated the confidence of King Menander in Buddhism. . . . In recent times – a remarkable series of debates was held in Sri Lanka. In a period of several years between 1866 and 1873, Christian priests and Buddhist monks led by Ven M Gunananda Thera (1823 – 1890) entered into a debate. Sri Lankan people and the world at large was stunned by the eloquence, knowledge and insight of Buddhist monks – in matters not only of Buddhism but also of Christianity. One can imagine the situation during those periods of time – when Christian missionaries thronged nearly every corner of the world riding on the back of wealth and power of the colonial rulers. The event widely covered by western media as a victory of the Thera – elevated the confidence of Sri Lankan people on their own religion – and Christian missionaries suffered a serious setback. It inspired rejuvenated interest in Buddhism – both in Asia and the West. In 1878, a book was published in USA entitled: The Great Debate – Buddhism and Christianity Face to Face. Col HS Olcott (1832 – 1907) was one of many Westerners – who was attracted by the book to embrace Buddhism – with their tireless contributions to the cause of Buddhism. In Asia – among others, Anagarika Dharmapala (1864 – 1934), Rahul Sankrityayan (1893 – 1963), Jiddu Krishnamurti (1895 – 1986) and BR Ambedkar (1891 – 1956) – were all inspired by the outcome of this debate. In 2017 (6 Nov 2017) New York Times published an opinion column written by Robert Wright (Professor of Science and Religion, and the author of the book Why Buddhism is True: The Science and Philosophy of Meditation and Enlightenment). It began by saying to the Western readers that: Buddhism Is More Western Than You Think . . . Interestingly Emptiness is found to be the fundamental truth – both in the minutest existence of matter and in the vastness of universe. Electrons move as a wave-particle duality (see The Quantum World) of uncertain motions in the space around the concentrated mass of nucleus in an atom. In the vastness of space in the universe – stars, planets, satellites and other objects orbit around massive objects such as the Black Holes – in the gravitational spacetime lattice (see Einstein’s Unruly Hair). In both of them – the space or spacetime is real only in the context of heavy or concentrated masses – therefore by itself each is empty of essence. Together, the system of mass and space defines the interdependent fluxes of energy in search for equilibrium. It is amazing to note how the metaphysical/spiritual principles brought to light by the Buddha about two and a half millennia ago – have converged at a fundamental level to the modern findings of physics. The Buddha was far ahead of his time – and what he saw as the metaphysical truth – is getting proved as the scientific truth. Sometimes the thought of Emptiness may evoke a sense of negativity in ordinary people’s mind. For example, if empty, why do this, why do that, etc. But the truth of Emptiness is far from such negative connotations. Let me attempt to see through the Buddha’s wisdom eye to explain why so – citing four simple examples to highlight some practical usefulness of this truth.

. . . The necessity of practicing the Five Precepts or Panchsila (described as the Five Basic Training Steps) came again and again in different Jataka Tales. I have highlighted their wider meanings in the Symmetry, Stability and Harmony piece. Thought of repeating them here for the sake of completeness, and also because of their importance:

. . . . . - by Dr. Dilip K. Barua, 10 July 2020

0 Comments

|

AuthorArchives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed